Abstract. Advanced simulations are becoming a common approach for dealing with complex fire safety problems. The use of specially developed software for fire and evacuation modelling allows fire safety problems to be solved in a way that was not possible just a few decades ago.

Performing advanced simulations requires a deep knowledge of both Fire Engineering and Fire Engineering Modelling. Engineers are often responsible for the life safety analysis, and are equipped with a number of tools to aid the design process. One challenge is to understand how to use such tools, but of equal and paramount importance is understanding their limitations, and thus when their use is not appropriate.

Nowadays advanced modelling forms a natural part of a Performance Based Design approach. Common areas of practice are Evacuation modelling and Fire & Smoke modelling and often a combination of both when assessing the fire safety performance of a building. Although both the means of escape for a building and a smoke control system could be designed following prescriptive requirements, many examples exist where a performance based approach is the only way forward and advanced computer models become an essential part of the Fire Safety Design.

Safe, robust, and practical solutions that account for human behaviour as well as advanced tools that predict the fire and smoke behaviour in a building are an essential component of any building design. Designers need to provide innovative designs whilst providing safe buildings.

In particular, the paper shows a series of case studies when advanced modelling were successfully utilized, these are:

- A large international airport

- A major interchange station

- An existing multipurpose building (heritage protected)

- A large logistics centre

The computer models used to perform the analyses were Pathfinder and Fire Dynamics Simulator. JVVA has used such models to evaluate, optimize and design singular buildings. The intention of this paper is to show how advanced modelling has been a vital part of the design process.

1. INTRODUCTION

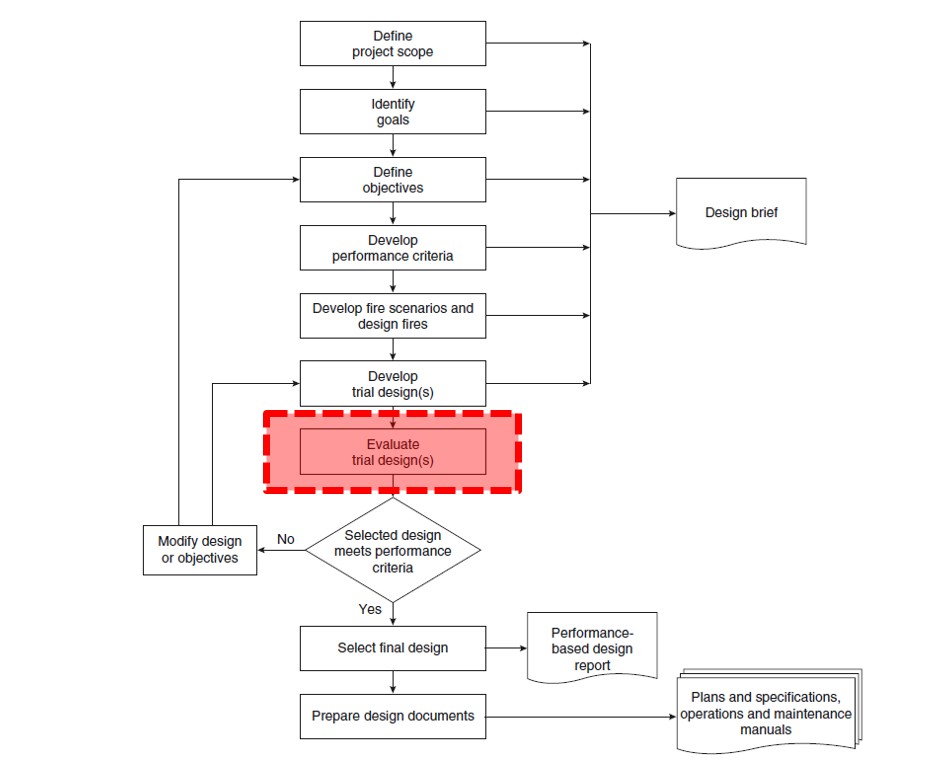

The increased use of performance-based design to develop fire safety solutions requires, for complex buildings, the use of advanced tools in order to get answers that would not have been possible using hand calculations and simplified models. Spaces can be particularly vast, evacuation paths particularly complicated and the architectural layout might impose restrictions in such a way that the prescriptive requirements cannot be fulfilled or, in some case, are just the wrong approach for a particular space and use. Within a complex performance-based fire safety project, advanced modelling covers an important part but only when it is well integrated into the overall design process. The graph below, from the SFPE Handbook, shows the Performance based design flowchart and in red where advanced modelling is situated within the overall process.

Each element of the flow chart are essential and responsible for the final outcome. An analysis undertaken through advanced modelling can be right or wrong depending on how those earlier elements were introduced in the overall analysis itself. Once the evaluation phase is reached in the performance base design process, it is time to get into the modelling exercise. Figure X, below, shows the process of determining the right model to be used in the analysis. The model can be a simple algebraic correlations that can be solved with a calculator, a zone models or lumped parameter models that represent a space as a small number of elements, to computational fluid dynamics or field models which approximate a space as a large number of discrete volumes.

Story of success exists where the use of performance-based design solutions has leaded to truly advanced solutions which have benefited the client and the building. Four examples have been selected and shown in this paper, outlining the role of the advanced modelling in the overall design process.

2. CASES STUDIES

2.1. Large Airport

The first example is the largest and busiest airport in Spain. The overall objective of the project was to evaluate the current fire safety level for all existing terminals. The study was specifically orientated at fire risks, the main objective was to identify additional fire safety measures that could be incorporated into the building and also quantify how these measures impacted on the current fire safety level.

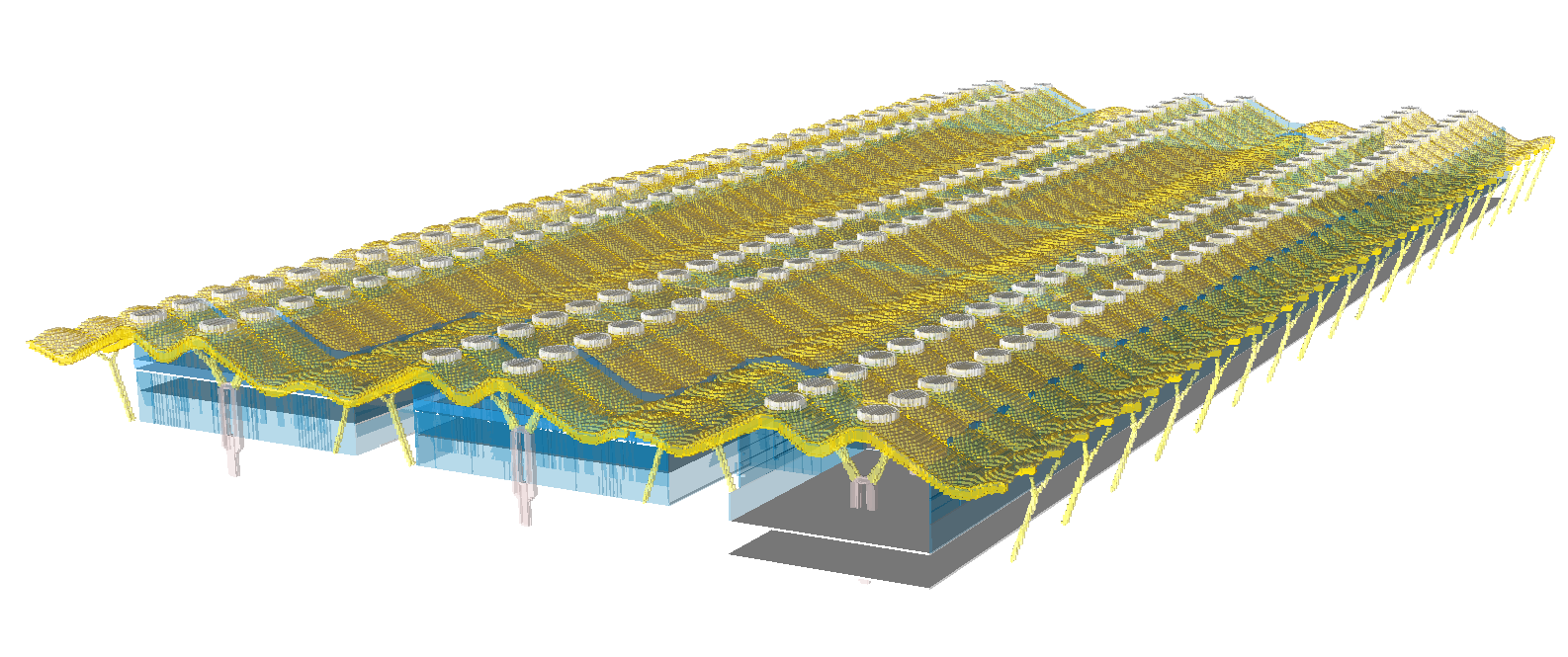

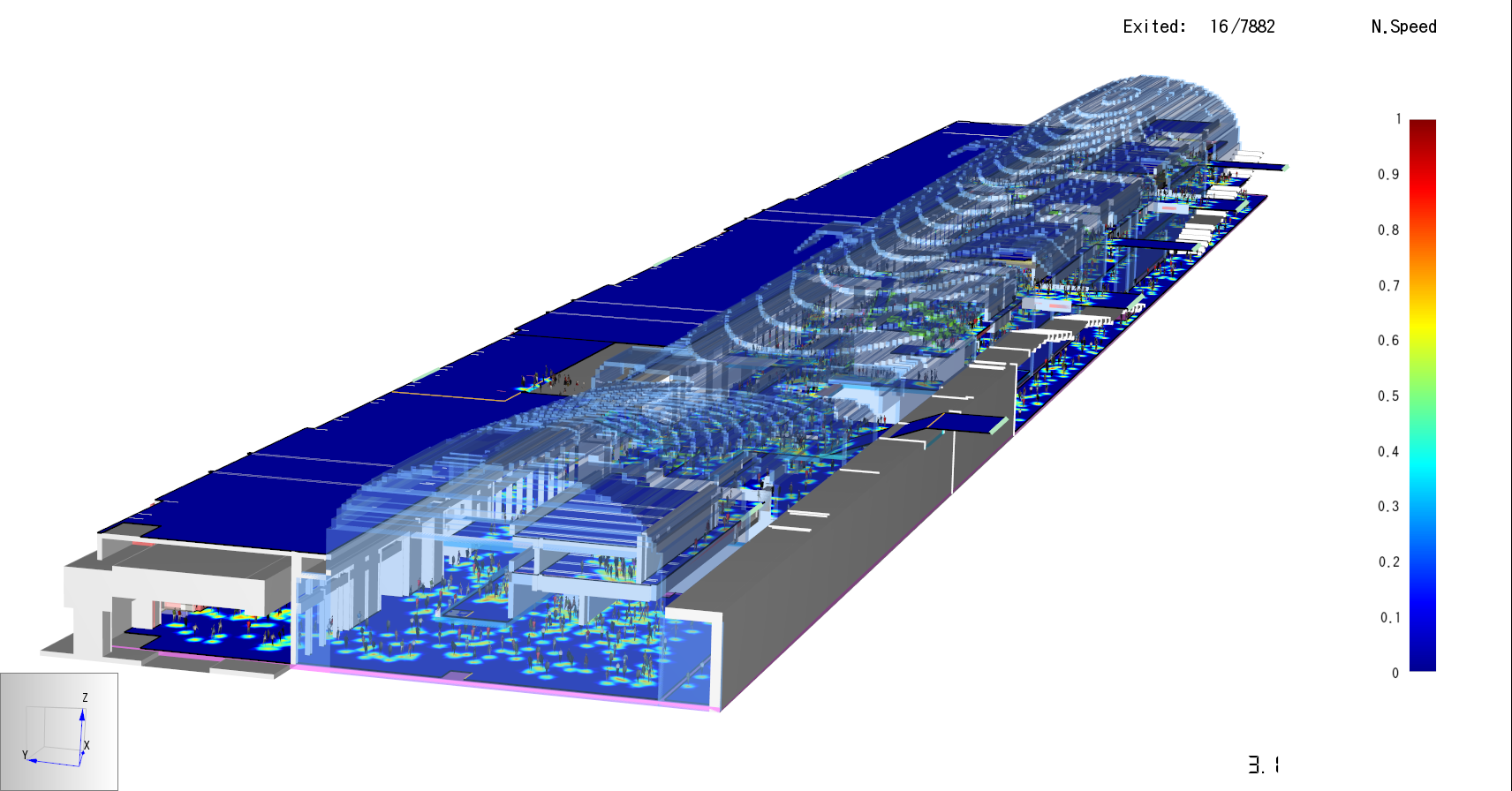

Specifically for this example, the largest terminal (T4) is shown. Due to the complexity and dimension of the building, advanced modelling was necessary. Both advanced evacuation analysis and Fire and Smoke modelling were performed for the terminal with the aim of evaluating the efficiency of the current evacuation routes together with the efficiency of the smoke control system, when available. For this analysis, Pathfinder 2015 was used for the evacuation modelling and FDS v.6.2.0 for the fire and smoke modelling. The first step in the analysis was to evaluate the existing configuration. The following image shows an example, commercial area in the airside departures level, during a simulated evacuation. As can be seen on the image a few large bottleneck areas were created using the current evaluation strategy for this level.

The analysis of the current configuration shown various conflictive points where people were stuck or simply the evacuation was not as fluid as it could have been. Minor changes have been introduced to the evacuation routes with almost no impact to the building with a substantial improvement of the building safety. By the increment of two corridors width together with the redirection of the part of the occupants toward the bridges instead of into a long corridors that was currently in use, the overall evacuation time was reduce by means of 30%.

In addition, there were several exits that were sub-utilized and did not really add value to the evacuation. By the introduction of a clearer wayfinding system (signage), omitting exits and creating additional exits (using existing non-used routes), there was a clear improvement in both evacuation time (reduced about 40 %) and in regards to the bottlenecks (which were heavily reduced as well). Together with the evacuation analysis, conditions for the occupants in case of fire have been assessed through fire and smoke modelling. The whole terminal has been modelled since it represented a single unique large compartment. The model was processed with FDS v.6.2.0, the domain was split into 30 different meshes assigned to 30 MPI processes, with a resolution varying from 0.10 m in the fire region up to 0.40 m in the regions far from the fire.

The overall results of the fire and smoke modelling shown that, despite the great volume of the terminal area, smoke had enough buoyancy to raise and fill the smoke reservoirs guaranteeing smoke layer stratification even with reasonably small fires with large spills (resulting in more and colder smoke).

This type of analysis could only be performed with the help of advanced modelling, especially the iterative analysis evaluating the benefit of the fire safety measures required a tool which had the needed features to show the changes that occurred. That said, the advanced modelling was only an element of the overall process and a lot of pre-work was required before the actual final simulation results could be obtained.

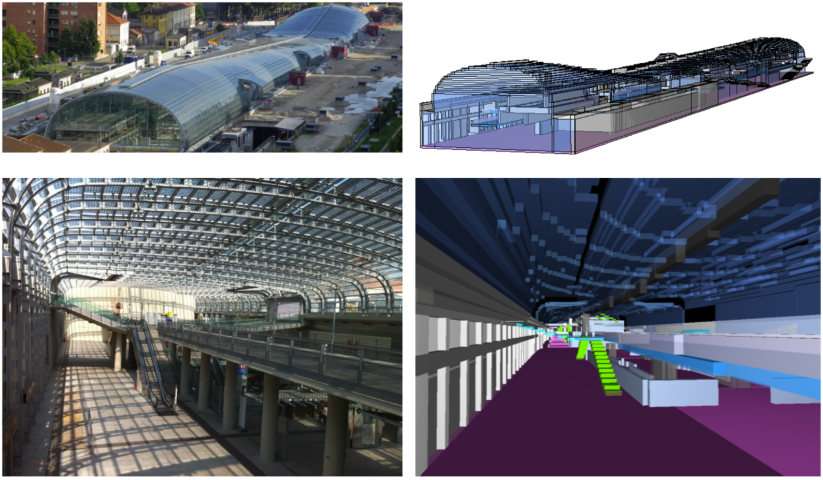

2.2. Interchange station

The second example is the largest interchange station in Turin, Italy. The station serves several national and international lines, this would include high speed trains, regional trains and Turin metropolitan trains, and there are also a metro line and several bus lines. The objective of the study was to evaluate the fire safety level for the station, and this to be performed for the whole building. This was done by using the well-established ASET vs RSET methodology. The smoke movement analysis (ASET) was required due to the nature of the volume, a 300-metre long, 19-metre high glass and steel structure was built above the tracks to create the new station, the space included different types of obstacles and similar. A particularity of the smoke analysis was that the existing tunnels had an influence on the ventilation conditions in the station and to improve the reliability of the results a multi-scale approach was used (principally to determine boundary conditions for the 3D analysis). Evacuation analysis was necessary due to the numerous merging flows coming from the platforms and from the building itself. The CFD model was processed with FDS v.6.0.0, the domain was split into 15 different meshes assigned to 15 MPI processes, with a resolution varying from 0.15 m in the fire region up to 0.30 m in the regions far from the fire.

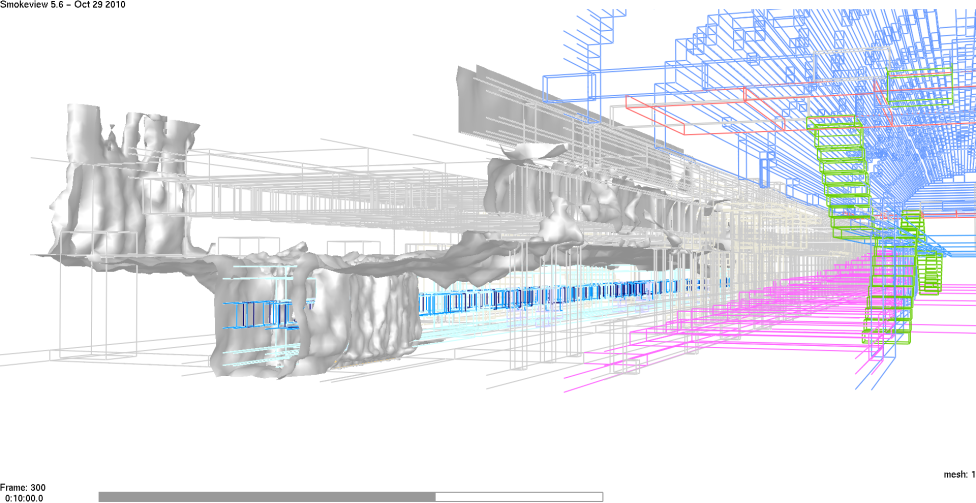

Before evaluating the design, the analysis required a dedicate pre-analysis so that the peculiarities of ventilation conditions could be taken into account. A robust sensitivity study of the input parameters was then performed, all with the objective to minimize uncertainty and maximize reliability of the results, this was especially important as natural ventilation of the station was used. The image below, shows through a visibility isosurface the effectiveness of the natural smoke control system particularly when passing through the natural shafts designed in the interface between the station buildings and the platforms.

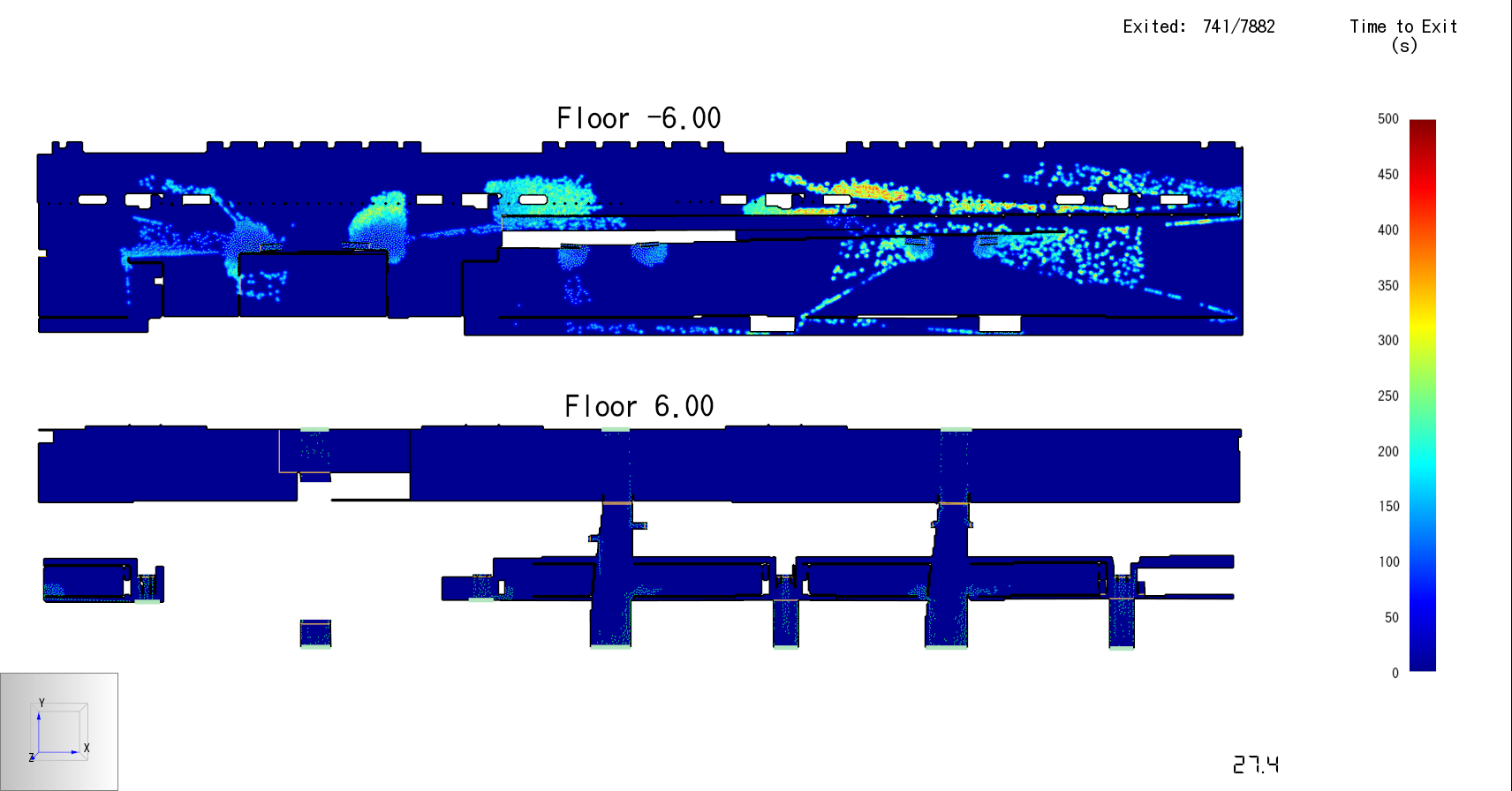

On the evacuation side, Pathfinder was used to determine the overall evacuation time of the station both due to legislative requirements and to evaluate those areas where the smoke was rapidly descending and affecting the evacuation routes.

This type of study could not have been performed (with reliable results) by empirical formulas, as the there is no way to take into account the particular boundary conditions due to the impact of other ventilation systems. On top of that such an approach would have introduced severe limitations, such as smoke reservoirs, physical compartments, etc., with no to little viability to be incorporated into the building design.

The benefit, or actually the need, of using computer modelling, to determine the smoke movement conditions and its interaction with the evacuation, for such a project is clear. The design vision could not have been achieved without such an approach.

2.3. High Rise Aparment Hotel

The third example is a heritage protected multiuse building in the centre of Madrid, Spain. Part of the building was to be transformed into an apartment hotel, the refurbishment was heavily limited due to the heritage status of the building, and no major design changes could be incorporated. The national legislation requires that for any major refurbishment the requirements of the current legislative document, for fire safety, must be fulfilled. This was a major problem for a relatively old existing building which is also heritage protected, the only viable option was to use a performance based approach. The national code requires the evacuation design to be based on the use of two independent evacuation stairs, the building was equipped with two evacuation stairs but they were not independent and they did not lead directly to outside, so there was a major problem regarding evacuation from the building. A significant part of the project was to evaluate, mainly from a viability point of view, all the different options that seemed to be possible. The main limitation being that no major refurbishment works could be introduced. The final solution was based on the concept of introducing a protected corridor connecting the two stairs and also to create a safe route to outside once leaving the final stair, on top of that the different fire safety systems were heavily improved. The following image gives an understanding of the concept solution developed. The two protected stairs are connected at basement level via a protected corridor, the final exit area have been compartmented from other uses and low fire load approach (basically non-existing fire load and reduced ignition sources) has been incorporated.

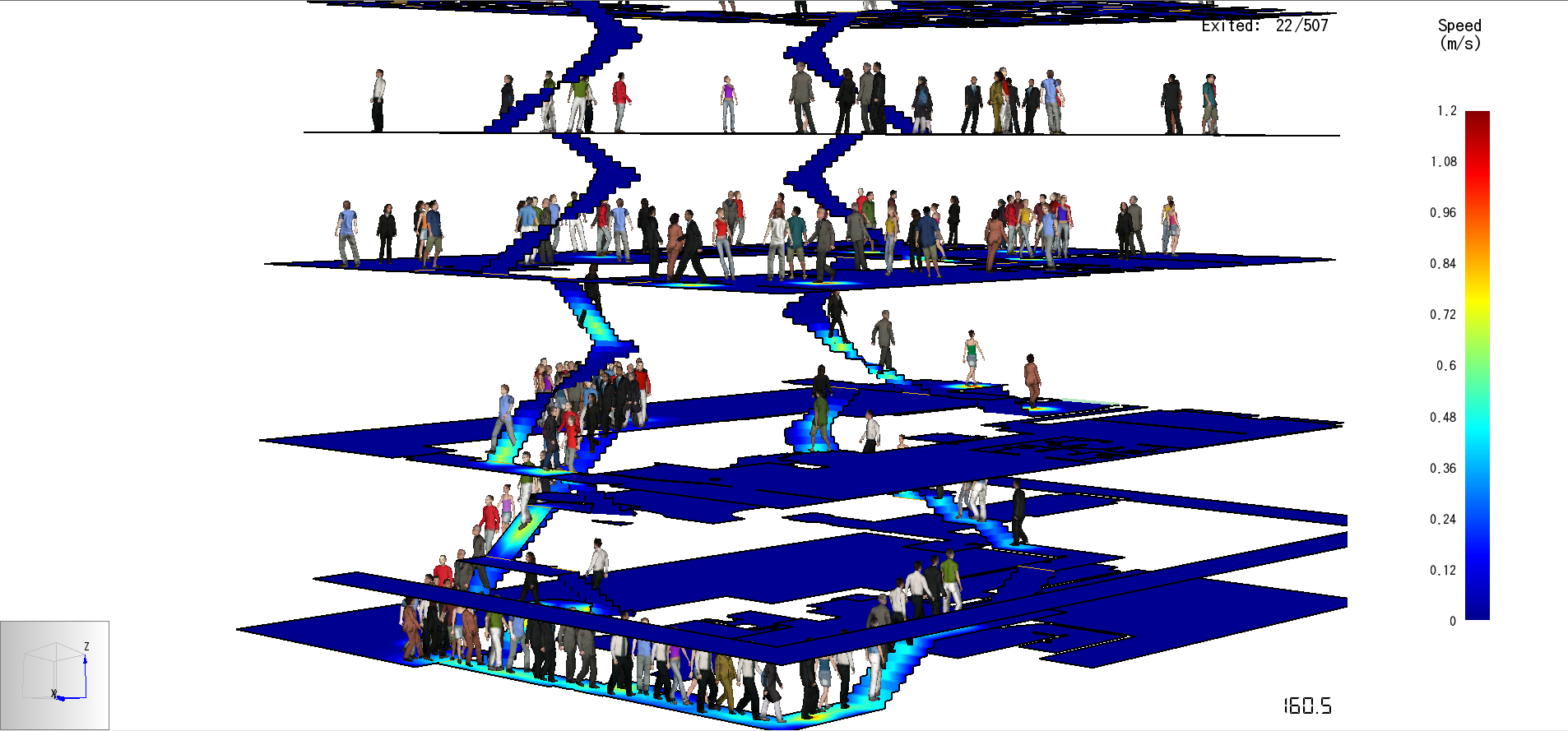

It was only when the concept solution was developed that advanced modelling was introduced in the process. It was indeed necessary to test how the evacuation from the building would work under different conditions. This was particularly important as the stairs received evacuees from different and independent parts of the building.

The evolution of Pathfinder and the new features introduced in Pathfinder 2015 made it possible to evaluate and quantify parameters that was not possible to evaluate before, such as speed, density, use, level of services in corridors and stairs and exit time. Those parameters was evaluated for all test cases and along the entire route. This type of evaluation could have only be performed by advanced analysis. The following images shows a few of these output parameters.

This analysis could not be done with simple people movement relationship since there are factors that cannot be taken into account for such an approach and they might have a significant impact on the end results. Only with the use of advanced computer modelling it was possible to achieve reliable results that could be used to take decisions regarding the design to be incorporated. Taking a broader view of the problem it can also be seen that this type of problems can only be solved through a performance based approach as the building could not comply with the legislative requirements.

2.4. Logistics centre

The last example is a large logistics centre. The objective of the study was to develop an alternative floor slab design, compared to the code requirement, so that the operation of the centre was not compromised. The national fire safety industrial code, specifically requirements regarding smoke movement, requires that intermediate floors have an opening area of at least 50% of the floor slab in the circulation areas, this is to permit smoke movement upwards. The operation of the centre, the use of trollies, needed a significantly less percentage of the floor to be open (steel mesh) due to operations procedures. Additionally a specific analysis was performed to justify the use of a single large smoke reservoir as the design and operation could not be achieved if smoke curtains were used. An advanced smoke movement analysis was performed for the logistics centre, a comparison methodology was used. A strict code compliant option was developed and several alternative options was tested against the code option. All comparison cases evaluated the evacuation conditions on all floors during a possible evacuation from the building. The model was processed with FDS v.6.0.0, the domain was split into 25 different meshes assigned to 25 MPI processes, with a resolution varying from 0.10 m in the fire region up to 0.40 m in the regions far from the fire.

The results clearly showed that the alternative solution chosen for the project was significantly safer than the code solution. The evacuation conditions (visibility and temperature) was kept better and for a longer time with the alternative solution compared with the code solution. The alternative solution did not only improve safety conditions in case of a fire it did also make possible an efficient operation of the logistics centre. The following images give an understanding of the different results obtained when comparing the code solution with the final alternative solution.

This is a case where the benefits or actually the need of using advanced modelling is clearly seen. An approach using empirical formulas could not have been used to evaluate the smoke movement in the building, and much less to compare different alternative design options. In this specific case an approach not based on advanced computer simulations could not have produced results that could be used to take important design decisions.

3. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

The role of modelling in PBD projects is clearly gaining more and more importance. There is also a clear trend that can be seen regarding the use of different types of models, it seems that a shift from using less advanced modelling to using more advanced modelling is taking place, even though it might not be necessary for the specific problem looked upon. It can be seen that models that used to be utilized for design in projects in the past, nowadays tends to be used a pre-analysis tools for the same type of projects. It might perfectly be that they could still be used for design but the market and clients, to some degree (at least for building design), want more advanced output (or with the risk of being blunt) a more visual and easily understandable output. This is often easily to achieve with the “new and modern” models when compared to their predecessors. So we are very likely looking at an increased use of more advanced modelling even if it would not be needed from a technical point of view.

Both models used and shown in this paper, Pathfinder and FDS, has substantially evolved during the years. The introduction of contour plot to track selected variables in Pathfinder, introduced in 2015 made Pathfinder one of the most powerful evacuation models on the market, supporting the needs of the engineering community. FDS and its continuous development, international use and its V&V support, made it the reference software used in the fire engineering community, the preprocessor Pyrosim became a must to have if doing projects with FDS.

All that being said, engineers must be aware that buildings might have been designed with the first versions of FDS and when Pathfinder was not as developed as it is now or probably not even born. Such buildings are (or at least should to some degree be) as safe as modern buildings built nowadays and this is because of the engineering judgement undertaken in the analysis. The engineering judgement is that virtue that comes with experience, knowledge and also having that common sense characteristic of an experienced engineer. Without this virtue, the results obtained by advanced models might be totally useless; and this is not because of the models themselves but because of the inaccurate approach to them.

Driving a car requires the driver to skillfully deal with the steering wheel, use the brake, the clutch the gear and the accelerator. Today in more and more cars the gear and the clutch have been replaced by the automatic gear, so the driver “only” needs to deal with the steering wheel, brake and accelerator. It doesn't matter the type of car you are driving.

What really matters is that driving involves so many other aspects, such as other cars circulating in the opposite direction, curves, slopes, velocity limits, signs to be read in real time, rear mirrors to be used simultaneously when looking at the road in front of you. Knowing how to deal with the controls is not enough to survive in a busy street, the same can be said about advanced modelling, it is not enough to understand the model the “surroundings” must also be known.

4. REFERENCES

[1] SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering (2016): 1785–1823. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2565-0_50.

[2] R.L.P. Custer, B.J. Meacham, “Introduction to Performance-Based Fire Safety”, 1997.

[3] Karlsson, Björn, and James Quintiere. “Enclosure Fire Dynamics.” Environmental & Energy Engineering (September 28, 1999). doi:10.1201/9781420050219.

[4] Society of Fire Protection Engineers. Guidelines for Substantiating a Fire Model for a Given Application. s.l. : SFPE, 2009.

[5] Society of Fire Protection Engineers, SFPE Eng. Guide to Performance-Based Fire Protection, 2nd Ed., 2007.

[6] K. McGrattan, S. Miles, Modeling Fires Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), in: SFPE Handb. Fire Prot. Eng., Springer New York, New York, NY, 2016: pp. 1034–1065. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2565-0_32.

[7] K. McGrattan, R. McDermott, J. Floyd, S. Hostikka, G. Forney, H. Baum, Computational fluid dynamics modelling of fire, Int. J. Comut. Fluid Dyn. 26 (2012) 349–361. doi:10.1080/10618562.2012.659663.

[8] K. McGrattan, S. Hostikka, R. McDermott, J. Floyd, C. Weinschenk, K. Overholt, Fire Dynamics Simulator User’s Guide, Sixth Edition, 2016. doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.1019.

[9] Fire Dynamics Simulator with Evacuation: FDS+Evac, Technical Reference and User’s Guide, 2015.

[10] Erica D. Kuligowski, Richard D. Peacockenand and Bryan L. Hoskins, “A Review of Building Evacuation Models 2nd Edition”, 2010.

[11] Principles of Fire Behavior – James G. Quintere, Delmar Publishers – 1998.

[12] Thunderhead Engineering, Pyrosim 2015 – User Guide

[13] Thunderhead Engineering, Pathfinder 2015 - Technical Reference.

[14] Thunderhead Engineering, Pathfinder 2016 - User Manual.

[15] Thunderhead Engineering, Pathfinder 2016 - Technical Reference.

[16] Thunderhead Engineering, Pathfinder 2016 - Verification and Validation.